The 1970s 3: PRODUCER FRED WEINTRAUP

PRODUCER FRED WEINTRAUP

Fred Weintraup was promoting a documentary that VARIETY labeled the THAT’S ENTERTAINMENT of the animal world. In one clip it actually had a group of dogs singing, singing in the rain. Definitely an off-beat project but, if you know Weintraup it didn’t seem all that unusual considering the man who had made it. The minute I walked into the hotel room I expected him to offer me a joint–or at least a toke. I assure you didn’t but I would have been surprised if he had. Weintraup was definitely what, in the 60s, was called cool. In fact, Mr. Weintraup was cool before it was cool to be cool. After some Hollywood chit-chat we got down to business.

EGAN—How did you start in the entertainment business?

WEINTRAUP—I ran a night club in the Greenwich Village called the Bitter End. Do you remember it.

EGAN—Sure. When I was in High School it was outside The Bitter End every weekend. That where I used to cop all my pot.

WEINTRAUP—Then I started managing acts and that took me out west where I eventually got a job at Warner brothers because they wanted someone who knew something about the music business. That was in the late 60s.

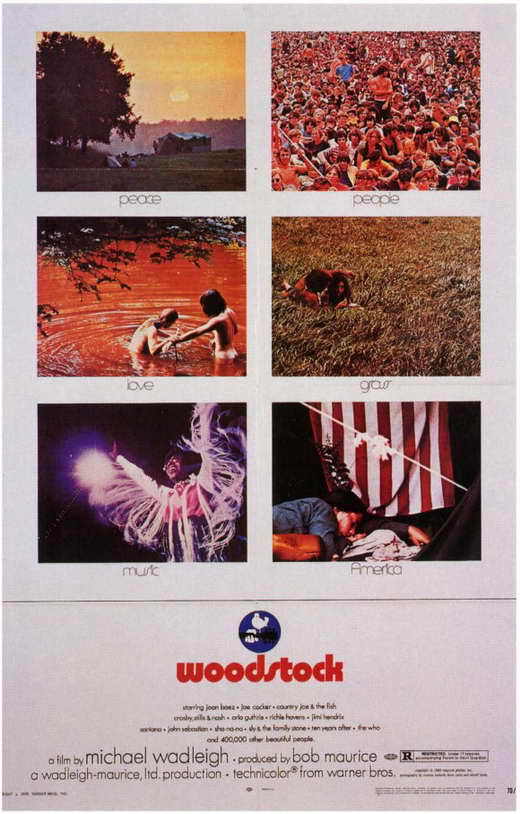

EGAN—Is that how you got involved with WOODSTOCK?

WEINTRAUP—These two guys, who had shot all this stuff at the concert, were trying to cut a deal with a studio so they could put the material together and get a release. The guys had absolutely no money and were in fucking debt. All they had was this 16 mm footage they shot at the concert. Because I was a music guy the studio had me take a look at it some of the footage. The minute I saw that stuff I knew it would make a great movie and I that’s what I told everyone there. But Warner Brothers was resistant. They didn’t want to make the movie. But I wouldn’t give up and finally I sat down with the head of the studio. He took out these charts he had. And he showed me, picture by picture, how concert movies never made any money. At that time the biggest grossing concert movie was MONTEREY POP and it hadn’t made shit. I told him that I didn’t give a shit about his charts and if he didn’t buy this movie I’d quit the studio and make it myself. And that’s how Warner Brothers decided to get involved with WOODSTOCK. Then there were fights on which stuff to use. The studio just wanted to use the concert stuff but I told them that it was the non concert stuff, the people stuff, that would make the movie.

EGAN—Like the Porto-san man.

The Porto-San Man

WEINTRAUP—Right. It was fucking great stuff. So someone made a decision to divide the film in half between the concert stuff and people stuff. And that’s how we came up with the three hour movie. It made 20 million bucks and got the studio to let me produce.

EGAN-What was your first hit.

WEINTRAUP—ENTER THE DRAGON.

EGAN—Tell me a little about making that film?

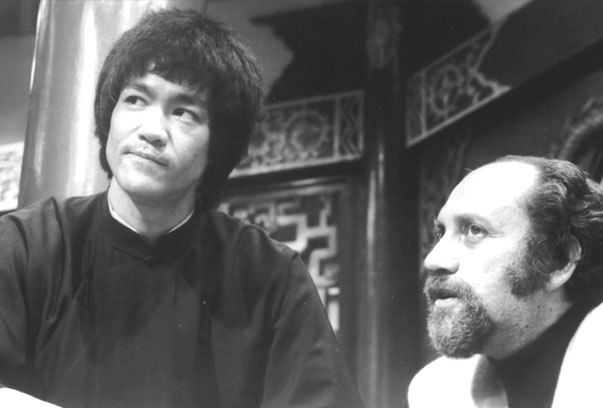

WEINTRAUP—Martial arts movies had been coming out of Hong King for a while and were making money. Because of this I was able to sell Warners into letting me produce a Kung Fu on a big budget—big budget for a KungFu thing. Warners made me hire John Saxon and Jim Kelly but for the third lead I wanted Bruce Lee. I kept telling them that if we didn’t have Bruce Lee, we wouldn’t have a movie, but everyone there kept telling me that American audiences would not accept a ‘chink’–that’s the word they used–as the star of a movie. No matter what I said, they wouldn’t listen to me and refused to hire Bruce. So, finally, in order to get them to let me use Bruce Lee, I had to give up my producing fee and instead, take points. They thought that they would teach me a lesson but, instead, they made me a fucking millionaire.

Weintraup With Bruce Lee On Enter The Dragon

EGAN—OK, let’s talk about previewing a movie. How do you go about doing it?

WEINTRAUP— I sometimes do 50 screenings until I get a film down to what we call a “no bathroom picture.” In other words no one gets up and goes to the bathroom. If a movie can keep people in their seats when they have to go to the bathroom, you got a movie.

EGAN—How do you feel when you love stuff that an audience makes you take out of the film?

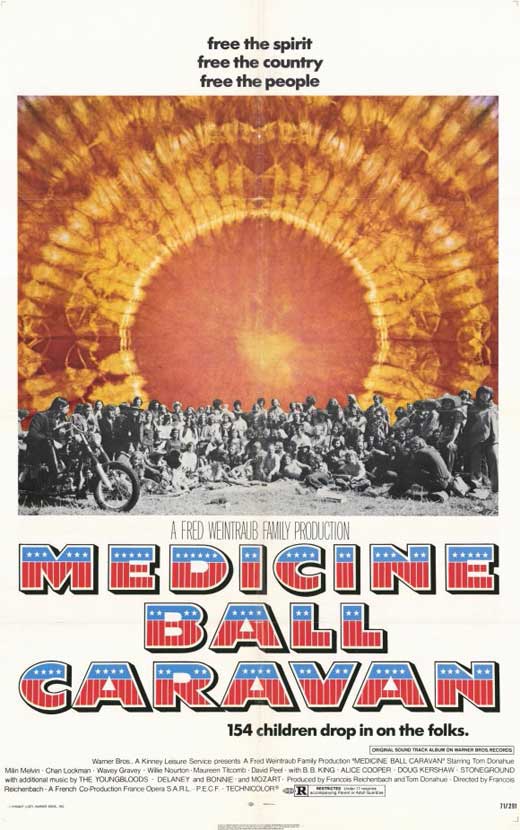

WEINTRAUP—Happens all the time. On WOODSTOCK I cut out things which were dynamite. I cut Janis Joplin out of that movie. In the editing room a film takes on a complete life of its own. Marty Scorsese started in the business as my editor on WOODSTOCK, and then was my associate producer and editor on a film I produced called MEDICINE BALL CARAVAN. I gave Marty his real start in the business producing and editing that movie. When Marty and I were looking at the rushes on that picture there was one scene that was so good that we cried. Then when we saw the picture later, in rough cut, the scene had to be taken out because it didn’t fit in with the total film.

Every director thinks he knows where he’s going when he shoots a movie, but he doesn’t. Billy Freidkin is a buddy of mine. Billy cut things out of THE EXORCIST that he really didn’t want take out of that movie but the stuff didn’t work. It’s crazy, but nobody really knows. Movies are a collective art form. A director isn’t really the director in America. I’m not talking about Fellini or Bergman. Those are different kinds of directors. Their movies begin and end with them. They’re not handed a movie by a producer like American directors.

EGAN—Who are the best producers?

WEINTRAUP—There’s Zanuck-Brown, Charttoff-Winkler, Heller and myself and maybe three or four others. We do about 30 percent of all the pictures that come out of Hollywood.

EGAN—Why so few?

WEINTRAUP—It’s a tough business.

EGAN—Why are you one of the few?

WEINTRAUP—-Because I’m lucky and because I look at the film business as a game that I love to play. Also, and this is an important part, I put my own money into my pictures and then after, while they’re being made or are finished, I sell them to the studios. In this way I stick my neck out on every picture that I make but I make my pictures the way I want to make them. There are only a few producers who do what I do, and as long as my films make money I can pretty much do what I want.

EGAN—Why do you think your pictures make money?

The Bitter End

WEINTRAUP—-When I screen a picture, I always watch the audience. I learned this from running The Bitter End in the 60s. The reason that my pictures do well is because I lived in that night club for ten years and learned to read an audience. I hired Woody Allen, Bill Cosby, Peter Paul and Mary. I even brought in Dick Cavett and Bob Dylan to perform there. I managed Neil Diamond and Joan Rivers. One time I had twenty artists under management. I had five other acts in the village who were as good as any of these other people but they didn’t make it.

Bob Dylan Performing In the 1960s

AEGAN—Why?

WEINTRAUP—I don’t know. I really can’t give you an answer to that. But, what I learned from The Bitter End was not to watch the artist. I learned to watch the audience. They always told me which

act was going to make it and which won’t. That is the key. And when I screen a picture, I do the same thing.

EGAN—OK, you make a movie. You show it to an audience and they walk out. How does it feel?

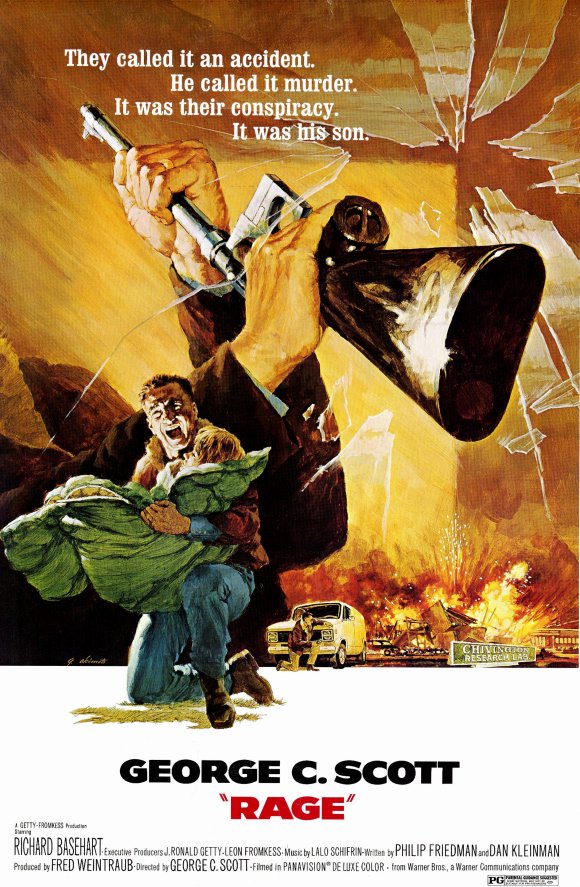

WEINTRAUP—It happens. I did a picture with George C. Scott called Rage.

EGAN—The one he directed? Boy, was that was a real stinker.

WEINTRAUP— It was pure death. Pure death.

EGAN-Scott blamed its failure on the studio who took it away from him and ruined it in the cutting.

WEINTRAUP—I know he says that and it’s bullshit. As soon as he finished shooting that picture, he knew it was a stinker. That’s why he didn’t show up at any of the post production meetings. Listen, I’ll say this right to his face. He’s full of crap. Everybody who was involved on that film knows that. He knew that he had a piece of shit and so he walked away from it and then blamed everyone else because it flopped. I had to finish that picture because no else would do it.

EGAN—Why would he say that?

WEINTRAUP—Simple. He couldn’t face the fact that he had made a bad picture. He didn’t even have the guts to go to the screenings. Scott’s a great dichotomy. He’s a macho bullshit guy and the best actor in the business, but when you get past that front, there’s nothing in there. What you see is all there is. That picture started with me. I got the idea after reading stories about an accidental nerve gas release and so I commissioned the writer and got the screenplay to George. Then he decided that he also wanted to direct it. When the picture was finally released I went to a theater where it was playing and there were four people in it. I couldn’t believe it. I cried and I got hysterical. I knew that first day I had a flop. I’ll tell you it was horrible.

EGAN—Because you liked the movie?

WEINTRAUP—It wasn’t a question of liking it or not liking it. I invested 18 months of my life in that picture. Producing films is not a question of liking or disliking the films you make. 18 months of my life went down the crapper. No one was going to go to that movie. It wasn’t going to make me any money and it was going to make it hard for me to raise money for my next film. This is why no one likes a flop. So, after that film I decided that I was never going to make a picture without thoroughly playing it off an audience. This is why I do as many previews as I do and a big reason why I’m as successful as I am.

EGAN-Sounds scary.

WEINTRAUP—Sure it’s scary, but a film is not anyone’s creation. All that auteur stuff that the French came up with and American critics won’t stop writing about is bullshit. That is not the film business. There are so many people and so many different things involved in making a film that you just can’t say that it’s this person or that person’s creation.

EGAN—So, if it’s not personal expression, what do you get out of making films?

WEINTRAUP—I’ll tell you. Joy. Personal joy. Three joys. One I love watching the rushes. There’s a film of mine shooting right now in the Philippines and I can’t wait to get back and look at the rushes. I worked on the script. I know all about it and I can’t wait for the rushes to come in so I can see what is happening with the material. The second joy comes when I see the first cut. That’s very exciting because at the first cut you know whether you have a film or you don’t. It’s that simple. It either works or it doesn’t and the rest is to try and do the best with what you have. And you know all this after you look at that first cut. The third joy is when the picture is released and you sit in an audience with a cold sweat waiting to see how that first paying audience will react. That audience will tell me whether the picture’s going to make money or not. The whole time I’m watching the movie, my wife’s got my hand and I’m shaking like a baby. It’s incredible. I can’ even describe the feeling.

EGAN—So, for you, the doing is everything. When it’s finished it’s over?

WEINTRAUP—Always. The doing is everything. The minute it’s done, I’m onto the next project.

EGAN—This is really interesting. I’m used to talking to actors or directors. And they have a very different take on the process.

WEINTRAUP—(Chuckling) Man, they’re so goddamn esoteric.

EGAN—But can’t you understand why a director screams when the film is taken out of his hands and re-cut.?

WEINTRAUP—First of all that “taking out of his hands” stuff, for the most part is bullshit. You don’t take a movie out of a director’s hand unless he can’t do the fucking job. Very seldom have I ever done that. Once the picture starts, I let the director take it all the way until I see the first cut. The director’s guild contract allows him, if he wants it, to make that first cut. So, I don’t usually interfere. Now, in most cases, if a director wants to stay with the picture past the first cut, I’m delighted as hell. It makes my job easier.

EGAN—Really. They don’t usually?

WEINTRAUP—In a lot of cases directors say they want to stay with a picture but when they see that they haven’t got a good picture, or a lot of the stuff they like will have to go if they want to make it a good picture, they walk off. That’s exactly what Scott did. Sitting there cutting a film isn’t easy and a lot of directors just don’t like to be hard on themselves. They see that as the producer’s job. That’s why the producer needs a different attitude. Let me give you an example. Dick Zanuck is a great producer. It’s my belief that he’s probably the best producer in the business.

Steven Spielberg And Richard Zanuck Making Jaws

EGAN—Tora Tora Tora.

WEINTRAUP—Hey, he did crap, too. Don’t get me wrong. We make movies. Half the stuff we make is crap.

EGAN—So, going into a movie what do you think about?

WEINTRAUP—As a producer I have a lot of considerations. If I’m going to hire, say Hal Asby for a picture, how fast is he going to direct it and how much will that cost me. Hal Ashy is a very slow director and his pictures always come in over schedule and over budget. They’re good pictures but they’re expensive. So I have to determine whether the price at which Ashy will deliver a picture is too high against the kind of money that picture might earn. If it is, before I even go into production, the picture’s going to be losing money.

EGAN—Right. These are money decisions. But the moment by moment creative choices don’t come from you. They can’t. It seems that you cannot allow yourself to become that involved because you might have to take the film apart if an audience doesn’t like it.

WEINTRAUP—Absolutely.

EGAN—But still, can’t you at least understand where the director is coming from? You talk about them as if they were children.

WEINTRAUP—(Chuckling) Because I know the truth about them. I work with them and have to deal with them all the time. Don’t get me wrong, they’re creative. But, so is the photographer. I know Haskell Wexler. The man is a genius. Yet, Milos Forman threw him off COOKOO’S NEST.

EGAN—They’re probably didn’t agree.

WEINTRAUP—Exactly. But, why couldn’t they get it together. I have directors who are very creative and for that matter, so are the actors. Well, actors; you know how they are. They’re all crazy.

EGAN—You get up there. You strip yourself naked in front of that camera. It’s not easy.

WEINTRAUP—Pretend I’m an actor. I don’t want to strip myself naked. I get up in front of the camera because I want that ego. I get in front of that camera because I can’t make it in life any other way. That’s George C. Scott. When you sit and talk to an actor in an interview he’ll say, “I had a moment and I lost it.” But you should sit with that actor in a screening room when he’s watching himself on screen. Do you know what he’ll say? He’ll tell the director, “Boy, do I look shitty there.” And the director says, “OK, I’ll take it out.” And directors are no better. Directors come to me all the time and say, “Do we have to put that piece in the picture. It really is shitty.” And I’m the one that has to tell them, “Look, does it work or doesn’t it. How do you feel about the totality of the picture.” They don’t think of a picture as a whole. They just think of it as scenes that will make them look good.

Do you know what’s the advantage that I have over most producers? I can tell whether a picture will cut together or not. Some directors are so involved with themselves they simply don’t have that kind of objectivity about their work. As a producer I can do three pictures at the same time and keep my objectivity towards those movies.

People are always asking me, “Why don’t you want to direct?” It’s very simple. I don’t have the personality that can sit in front of the thing and talk to it 25 hours a day. That’s what a director must do. He can’t think about anything else. He can’t go off somewhere else. He’s got to stay with the picture until it’s done. On top of that all directors need to be great bullshit artists. They have to be in order to handle, and that’s the only word for it, the nutty people that they have to deal with in order to make a movie. Marty Scorsese is the best bullshit artist that you will ever meet in this business. I don’t mean he’s dishonest. I mean he knows what to tell an actor to get them to do what he wants. It’s really a talent. When you put the concentration together with the bullshit, you’ll have yourself a guy who’ll make it as a great director in this business.

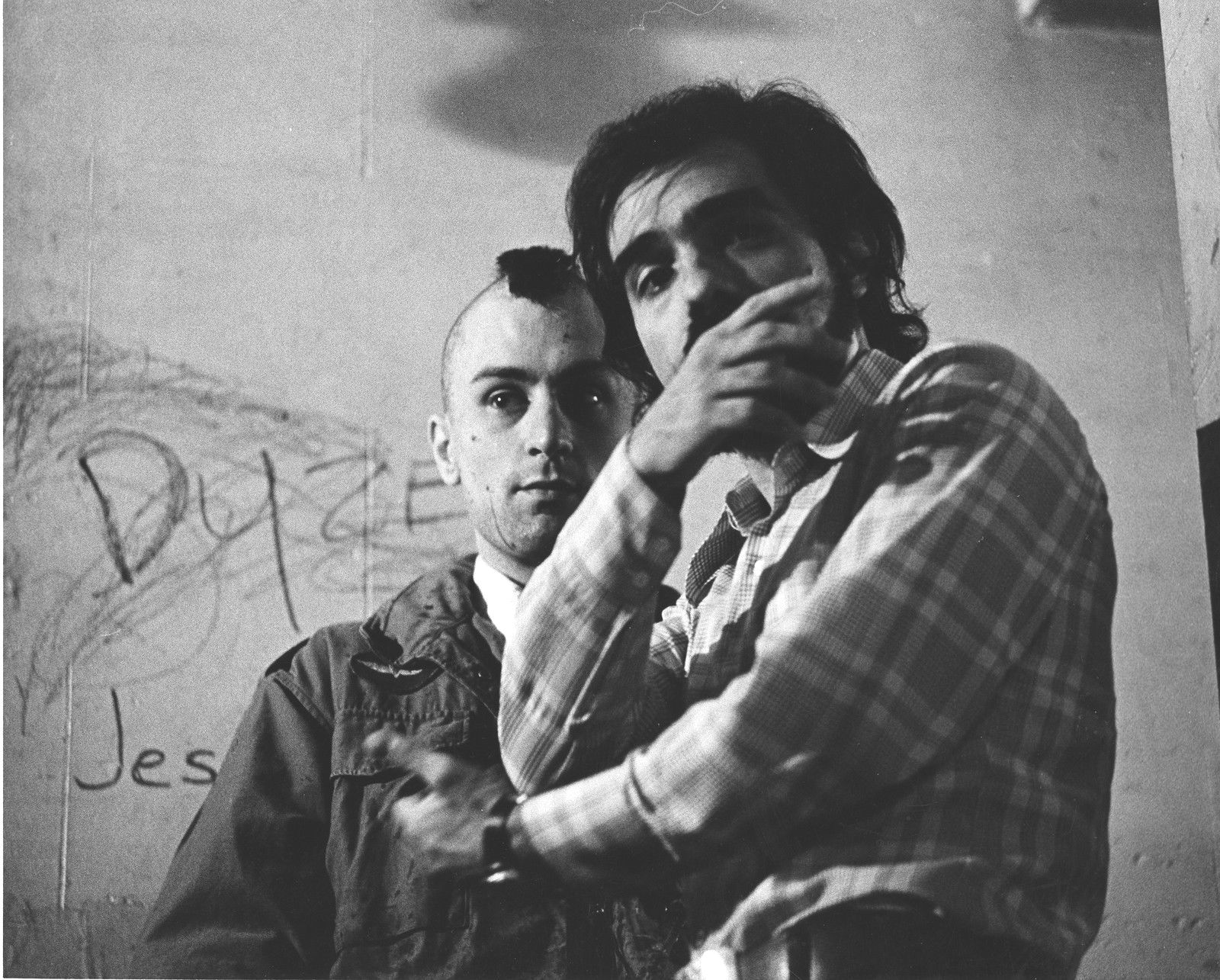

Martin Scorsese Directing Robert De Niro In Taxi Driver

EGAN—I think the pressures on a director while shooting most be murderous.

WEINTRAUP—During the filming of a picture Marty Scorsese literally gets sick. Think of what the director’s job is. He must take a series of isolated incidents that are not filmed sequentially and be able to film them in such a way that when they’re cut together they will look like something that makes sense, works with an audience and can actually get people to pay money to see it.

EGAN—How the hell do they do it?

WEINTRAUP—Well, some of them do it by shooting so much footage that they can finally edit it into something. Others like Hitchcock or Ford, plan it all out before they shoot and cut it in the camera. Hitchock’s so visual, and let me tell you it’s all business with that guy, that he can actually see the finished picture before he shoots it. Now, when you’re talking about someone like Hitchcock, you’re talking about a real film maker.

EGAN—Yea. He’s a genius.

WEINTRAUP—That’s the problem with that word. The problem is that we’re in a business.

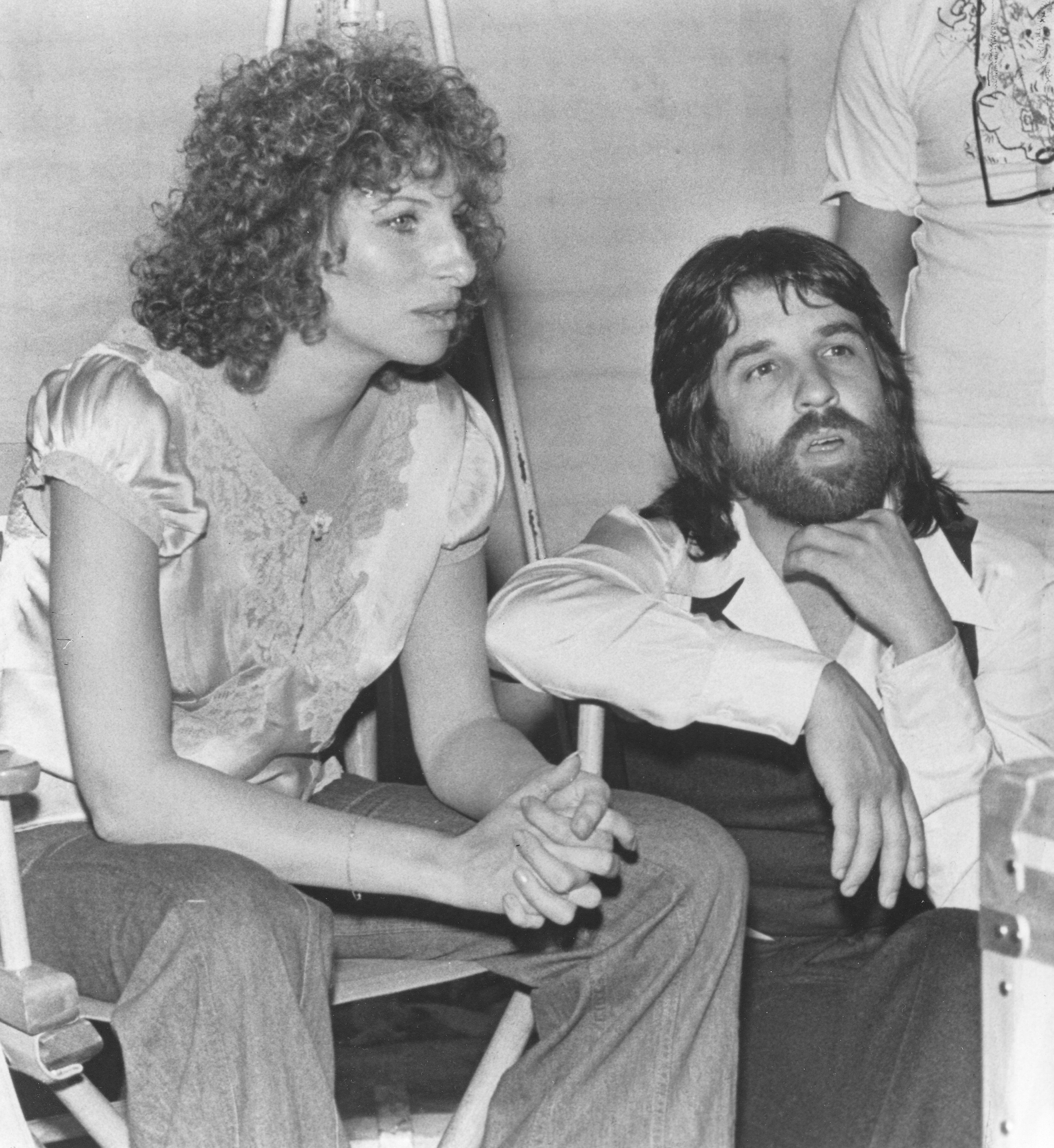

EGAN—I was in Phoenix and saw Streisand and Jon Peters….

WEINTRAUP—You can’t judge a producer by him. Peter’s never done a picture before. He’s learning. He’s a kid from the streets with a good street sense. What he’s doing now is keeping Streisand happy and she lets him produce her movie.

Barbara Streisand And Producer Jon Peters On A Star Is Born

EGAN—He couldn’t be doing it if it wasn’t for her?

WEINTRAUP—Well, of course. But that’s with all producers in town. Some guys are friends of Steve McQueen or Robert Redford or Ali MacGraw. How do guys become producers? Is there some producer’s school out there?

EGAN—Peter’s was planning to direct the film. He was a beautician; what does he know about directing a movie?

WEINTRAUP—You’re working on the assumption that directing is difficult.

EGAN—I also work under the assumption that producing is difficult.

WEINTRAUP—(Smiled slyly) Not at all. I’ll tell you, producing is fun. I find movies a wonderful business to be in.

EGAN—Until your films lose money.

WEINTRAUP—Well, then I won’t be able to make any more movies. I don’t kid myself about that. The day that my films are not profitable over a long period of time; or Dick Zanuck isn’t or any other producer doesn’t have a package the studios want, none of us will be in the business. I’ve been very lucky. I’ve always been a little ahead of the market. I have instinct for that kind of thing. But I think the business is absolutely delicious.

WEINTRAUP—Tell me the truth, what do you really care about, then?

WEINTRAUP—My horses. I raise the best Clydesdales in the country. If you want to know the truth, that’s what I really care about. If I ever started to care about the business I’m in that I couldn’t walk away when it was time for me to leave, I’d be as bad off as the directors and actors that I have to work with.