THE MOON WAS BLUE PART 1: THE MOTION PICTURE PRODUCTION CODE AND OTTO PREMINGER’S "THE MOON IS BLUE"

THE MOON WAS VERY BLUE

PART ONE

This was actually my first attempt at prose writing. It was for a book proposal. I re-read and although it tell a fascinating story it shows my academic roots. I would soon move beyond this but the piece still remains quite interesting.

******

Released in in 1953, The Moon is Blue—a light, little comedy of manners –was met with the loudest and most rabid censorship furor in the history of the American film. Today, it is hard to believe but churches, prosecutors, police, public officials, clergy and even children’s groups stood on one side of the fight while a film company, a producer-director, three theatre chains and the United States Supreme Court stood on the other. The Moon Is Blue’s release became a showdown between producer-director Otto Preminger and Joseph Breen, head of the Hollywood Production Code and Hollywood’s censor. Preminger was fighting for the freedom to make his films his way and Breen to retain control of the content of American motion pictures. Eventually, this contest of would change American cinema forever.

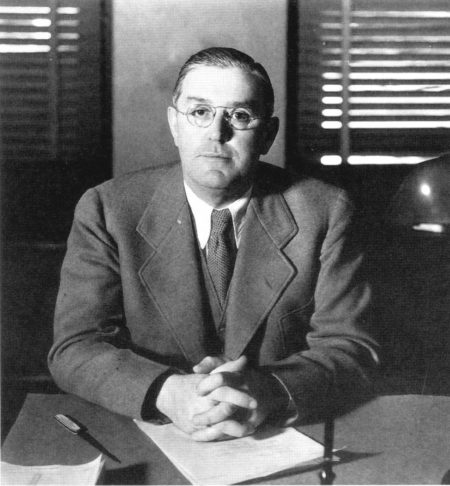

Director Otto Preminger

Otto Preminger hadn’t always been in a position to take on someone as powerful as Joseph Breen. It was an evolution begun in the late 1930s when, following his meteoric rise in Viennese theatre, Preminger’s first invitation to Hollywood had ended in disaster. He managed to direct two films before his famous temper and a shouting match with Fox’s head of production, Darryl Zanuck, got Preminger blackballed. It was 1937. Hitler was preparing to march into Austria and Preminger was Jewish. So, with a return to Vienna out of the question, Preminger spent the next seven directing on Broadway.

Preminger and Joan Bennett in Margin For Error: It Brought Preminger Back To Fox

Not a man who allowed himself to be down long, 1942 found Preminger back at Fox in 1943 producing and then, taking over direction of the murder mystery Laura. Once again finding himself battling Zanuck, this time Preminger controlled his temper and Laura went on to be a hit. The film’s success earned Preminger a lucrative producer/director contract at the studio.

As a Fox producer Preminger had a degree of control over what he directed but the overriding creative sensibility at the studio was Darryl Zanuck’s. From the start it piqued Preminger to be in Zanuck’s shadow. In Vienna at age of 26 this former wunderkinder had replaced Max Reinhardt, Europe’s greatest theatrical producer, and implementing his own vision had achieved great success and enormous fame. After experiencing creative freedom and public celebrity, being a Zanuck man, no matter how much money he was paid, was not Preminger’s cup of tea. So, in 1950 Preminger decided it was time for a change and renegotiated his contract. His is His 500,000 dollar year salary was halved giving him six months each year to do what he wanted. And, what Preminger wanted during Winter-Spring 1951 was to direct two plays in New York. The first was a two performance flop. The second was The Moon Is Blue.

Preminger Directing Ana Andrews And Henry Fonda in Daisy Kenyan

The Moon Is Blue, written by F. Hugh Herbert, opened at the Henry Miller Theatre on March 8, 1951. Starring Barbara Bel Geddes, Barry Nelson and Donald Cook it was Herbert’s fifth Broadway comedy. The writer, also a Viennese emigre, was a master of light comedy—his play Kiss And Tell had run 983 performances—and so Preminger had high hopes for The Moon Is Blue.

F. Hugh Herbert

What Herbert called his “provocative comedy of purity” tells the story of a “pick-up”. On the observation deck of the Empire State Building pretty Patty O’Neill meets handsome Don Gresham. She is a candid if somewhat wide-eyed 22 year old and he is a successful but cynical architect. Opposites attract and Don invites her to dinner. When he suggests stopping off at his apartment to fix a button Patty candidly asks if he plans to seduce her. She’s a virgin and plans to remain so. Disarmed by her forthrightness Don promises not to try. The questions, “Will he keep his promise?” and “Will she give in if he doesn’t?” provide the underlying tension throughout the second half of the play.

At the apartment Patty offers to make Don dinner. While Don is out getting groceries David Slater drops by. The father of Cynthia Slater, Don’s ex-fiancé, David is a middle aged ladies’ man on the make. He turns on the charm and Patty invites him to stay for dinner. While the three are eating Patty accidentally soils her dress and changes into Don’s dressing gown. When Don is called away by jealous Cynthia, Slater attempts to seduce Patty. He eventually proposes marriage and offers Patty a no strings attached gift of $600. She declines the marriage proposal but accepts the $600.

Don returns just as Patty gives David an appreciative kiss. Thinking the worst Don accuses Patty of giving in to David’s wiles. They argue and, while Patty changes to leave, David heads back to his apartment. A moment later Patty’s father, a New York City policeman, shows up and, thinking the worst, knocks Don unconscious and takes Patty home. Later that night Patty returns to apologize but just as she and Don are about to make up David appears. Now David thinks the worst. When Don finds out about the $600 he suddenly becomes jealous, doesn’t believe any of Patty’s explanations and finally asks her to leave. The next day Don and Patty once again run into each other on the Empire State Building. After all the misunderstandings are finally cleared up, Don proposes marriage and Patty accepts.

Barbara Bel Gaddis, Barry Nelson and Donald Cook On Stage In The Moon Is Blue.

The play’s characters and plot mechanics weren’t particularly fresh but the dialogue and perspective Herbert gave his characters, especially David Slater, were. Perhaps the most refreshing aspect of the play was its presentation of Patty O’Neill. She was a modern, practical young woman who spoke her mind. In 1951, even for sophisticated theatre audiences, it was quite novel to hear phrases like “men are usually so bored by virgins” and the words “pregnant”, “seduction”, “mistress” and “professional virgin” coming out of the mouth of a pert 22 year old.

Broadway critics found Herbert’s “romantic trifle” humorous but, like most of his comedies, insubstantial. However, the play was exactly what theatre audiences were looking for and The Moon Is Blue became one of the biggest hits of the 50/51 Broadway season. Playing to packed houses the show ran 924 performances and spawned additional companies in Chicago, San Francisco and London.

Preminger had lucked upon a bonanza. When the Hollywood offers started coming in he persuaded Herbert to hold off. If they produced The Moon Is Blue independently they could reap a Lion’s share of the film’s potential profits. Herbert agreed and the two formed Carlyle Productions and hired themselves as producers. Without spending a cent Preminger was now an independent producer planning to film one of Broadway’s hottest properties.

******

By 1950 the American film industry was experiencing a mid-life crisis. Due to a Supreme Court’s decision mandating film companies divest themselves of their theatre chain, the studio production system Preminger was trying to escape was in transition. Studio owned theaters, no longer required to play a specific studio’s product, could now pick and choose the films they exhibited. Overnight millions of dollars in guaranteed studio profits disappeared. Adding bad to worse, by the early 1950s television had become part of the equation and film companies found themselves competing for a movie audience cut in half by TV.

With less money coming in studios could no longer afford the overhead a movie factory required. So, first came cost cutting, then budgets were slashed. Eventually B picture production was eliminated. Finally there were firings; initially a trickle, then wholescale. It wasn’t long before studios could no longer make their films with the talent they had under contract. More and more stars, directors and writers were working free-lance; signing one and two picture nonexclusive deals. Contract talent always at the immediate and unquestioning disposal of the film studios were now free to pick and choose their properties. A buyer’s market had transformed into a seller’s.

It was in this changing landscape that Otto Preminger was preparing to produce and direct The Moon Is Blue. If Moon proved a hit he would achieve his dream of independent production. An iffy proposition at best. Fortunately, Preminger was gambling on the merits and established popularity of a hit Broadway show. There was just one snag.

Preminger knew the play’s sexual content, content sophisticated theatre audiences took for granted, would have a difficult time passing Hollywood’s censorship code. Joe Breen, Production Code Administrator and Hollywood’s censor, had already advised two studios interested in The Moon Is Blue that the play was unacceptable screen material. If Breen decided the material in Moon was inappropriate he could demand it be cut or edited. If Preminger declined to make these cuts Breen would withhold the Motion Picture Producer’s Association (MPPA) Seal. This certificate of approval was required by all the large theatre circuits and without those important bookings a film couldn’t hope to earn a profit.

This would be a difficult if impossible compromise for the director. In The Moon Is Blue the whole was greater than the sum of its parts. The play’s success depended on a fragile mix of characterization, wry perspective and winsome humor. This delicate theatrical soufflé could collapse if any element in the recipe was altered. As so much was riding on Moon it was not a mix Preminger was willing to tamper with. Consequently, he and Herbert had decided to make a faithful—explicit dialogue and all—version of the play.

If Breen wouldn’t give Moon the MPPA Seal Preminger would have to prepare himself for the unthinkable. He would have to release his film without the seal and battle Joe Breen and the Production Code.

Joseph Breen

Joseph Ignatius Breen’s incarnation as Hollywood censor began twenty five years earlier when he met fellow Irish Catholic, Martin Quigley. Joe Breen was already nearing middle age and years of fruitless career hopping had made him hungry for success. He was now Public Relations Director for the 1926 Chicago Catholic Eucharistic Congress. Martin Quigley was the publisher of the influential trade Journal MOTION PICTURE HERALD. Seeing a use for each other, these two ambitious men struck up a mutually beneficial friendship. Breen wanted access to Quigley’s film industry connections and Quigley wanted Breen’s carefully cultivated influence with important power brokers within the Catholic Church.

Quigley’s ambitions were aimed a bit higher than Breen’s. Initially, Breen just wanted to get ahead but Martin Quigley wanted nothing less than the moral leadership of the American motion picture industry. It was through his friend Will Hays, President of Hollywood’s Motion Picture Producer and Distributors Association (MPPDA), that Quigley found the means. The publisher was going to put an end to local movie censorship by having have film companies censor themselves; their guidelines coming from a specially prepared rule book. And who would write this rule book? Why Martin Quigley, of course.

It would be more than a rule book, though. Quigley felt the motion picture industry needed a moral doctrine out of whose philosophy would emanate motion pictures designed to uplift and not demean the moral standard of America. What Quigley didn’t say—what was implicit the moment pen touched paper—was that this philosophy would be steeped in Quigley’s own parochial Catholic morality.

Martin Quickly knew that, for this “Motion Picture Production Code” to gain approval both in Hollywood and the boondocks, it needed more than Martin Quigley’s name behind it, it needed the imprimatur of the Catholic Church. Thus, the Code needed to be co-authored by a priest sanctioned by the Church and here is where he needed Joe Breen. Breen, a master of persuasion, knew all the right arguments and all the right Church leaders with whom to speak. So, he instructed Quigley on the fine points of manipulating cautious Church leaders and the publisher obtained as his co-author the Jesuit priest Father Daniel Lord.

When Quigley and Lord completed their Motion Picture Production Code it was handed to Will Hays. This was exactly what Hays needed to put an end to calls for governmental Censorship and in February 1930 the MPPA Board adopted it. At Quigley’s suggestion a grateful Hays appointed Joe Breen Public Relations Director for the new Production Code and Breen had his foot in the door.

The MPPDA started out life in 1922 as a public relations ruse. For two years the Arbuckle and Desmond Taylor murder scandals as well as the drug abuse deaths of two important stars had been making headlines with Hollywood labeled America’s Sodom on the Pacific. This may seem funny today but in 1922 the film colony’s notoriety had many prominent “blue nose” opinion makers alarmed. They feared that movies made in a “morally degenerate” community might harm American morals. How could these moralists “stem this tide” of depravity? When in doubt, pass a law. Bills advocating film censorship were proposed and Motion Picture executives were worried. They weren’t worried about depravity, they were worried that Washington would respond to this public outcry with an investigation.

If there was one thing film the industry didn’t want was a Washington committee poking its nose into the film industry’s highly “creative” business practices. During the early 20s Hollywood was using conservative Wall Street money to finance studio and theatre expansion. Film executives knew that this money would run for cover the minute a Washington investigation reared its head.

Will Hays

So, the Postmaster of the United States, Will Hays, was hired to head up the MPPDA. A protestant church elder with an impeccable moral reputation, Hays’ years in Washington had made him the perfect lobbyist. Preaching the gospel of self-regulation Hays soon had Washington pacified, censorship boards assured “clean” pictures were on the way and Wall Street told to keep their money pouring in.

When things cooled down Hollywood went back to business as usual without much interference from Hays. It wasn’t until the late twenties that Hays actually instituted a “clean up” program. Local censor boards were hacking up films and these mutilated prints were hurting revenue. As a remedy Hays created something called the Studio Relations Board and hired Colonel Jason Joy to head the office. Joy developed a “Don’ts and Be Carefuls” list compiled from the different state censorship codes and sent them to the studios. What did the studios do? The ignored Joy and his list.

It remained that way until 1929. Radio’s growing popularity was cutting into movie revenue, and desperate to prop up sagging box office, studios began releasing pictures rife with sexual situations and containing partial nudity in the form of skimpy woman’s bathing suits and skimpier lingerie. Of course audiences loved it and of course churches across the country were in an uproar. Then in March the industry’s worst fears were realized. A bill was introduced in Congress proposing to make the entire film industry answerable to the Federal Trade Commission. This wasn’t a Washington Committee, this was full scale Washington regulation.

Once again panic set in and once again Hays was called to the rescue. This time though, he was armed with the Motion Picture Production code and had Joe Breen running interference. Breen worked out of Martin Quigley’s Chicago office and did his job with unceasing energy and devotion. While Hays sold the Code to Hollywood, Breen hammered at the Press, the Church and the public. By the spring of 1932 the two men had PR’d the censorship howls down to whispers.

Breen was a rambunctious bear of an Irishman who had absolutely no scruples when it came to getting the job done. He was impossible to intimidate and when it was needed could charm or battle his way to a winning position. Hays needed a man in the Hollywood office; a man loyal to him who would not only be his eyes and ears but also tough enough to stand up to producers. Breen was made to order and Hays promoted him to head of public relations for the MPPDA’s West Coast office.

I

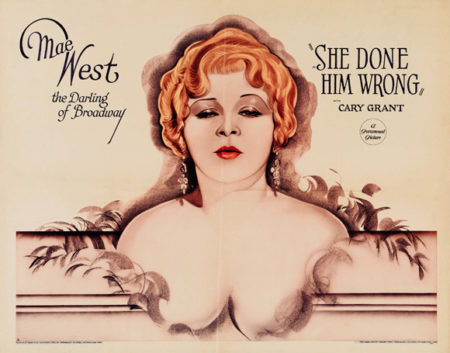

n the spring of 1932 the country was in the midst of the Great Depression. Theatre attendance had plunged and several film companies were on the brink of bankruptcy. By December twenty percent of the film theatres in the United States were closed. Literally fighting for their lives the studios did the only thing they could do. They made pictures the public wanted to see and a stream of “sex pictures” were released, spear-headed by the February 1933 opening of Mae West’s She Done Him Wrong. It was a “red-hot smash.”

Audiences delighted in West and her personal and screen philosophy that sex in any form was not only healthy but should be fun. This utter disregard for accepted sexual mores about sex and marriage had irate religious leaders furious. Colonel Joy’s replacement, James Wingate, had tried to force the studio to remove some of the racier material but after a lot of lip service Paramount sent out She Done Him Wrong exactly the way it wanted.

Besides bringing on another call for film censorship, She Done Him Wrong and other films like it were clear evidence that the Production Code was failing. Code officials could argue and plead but with no means of enforcement The Code, film producers pretty much did as they pleased. Will Hays and Joe Breen were beside themselves. If something wasn’t done and wasn’t done soon censorship might be taken out of the hands of Hollywood and the MPPDA.

Then, during the summer and fall of 1933, a sequence of events presented Breen with a way out of this quagmire. Several Catholic organizations had stopped talking about censorship. They were now talking about boycott. Using the threat of incurring sin, Church leaders could compel their congregations to stay away from film theatres. This is exactly what they were threatening and producers all over Hollywood were worried. Boycotts meant empty theatre seats. Empty theatre seats meant lost revenue.

Breen persuaded Hays to let him handle this “Catholic Crisis” and in December 1933 Hays appointed Breen head of the MPPDA’s West Coast Office. Jack Vizzard, a Production Code officer during the 40s and 50s, believed Breen had already made the decision to use this threat of a Church boycott to coerce producers into adopting the Production Code. Vizzard was certain that Breen and Quigley had met surreptitiously with Church leaders and persuaded them to form a national boycotting organization. True or not, on April 11th 1934 the Episcopal Committee formed The Legion Of Decency. It would be composed of Catholics who pledged to avoid films designated by the Legion as either offensive or condemned.

For Breen the Legion was a godsend. He used it and other threats of boycott to brew up uneasiness among studio executives. Then he and Hays used this growing apprehension to give credence to their claim that only adoption of the Code could prevent the Church from barring millions of Catholics from movie theatres. With all those empty seats looming, frightened film executives finally capitulated.

Once the agreement was signed Hays, guided by Breen, made it mandatory for all MPPDA member studios to submit all treatments, scripts and completed films to the newly named Production Code Administration Office (PCA) for a Seal of approval. Moreover all theatres owned by MPPDA members were forbidden to play any film which had not earned a Seal. Without those theatres a film was virtually un-releasable and in short order banks made Seal approval a requirement for production loans.

What Breen had done was to brilliantly maneuver a voluntary code of self-regulation into a mandatory code of censorship. In addition, every film receiving a Seal was required to pay the Code Office, on a sliding scale, a fee ranging from 84 to 3,000 dollars depending on its budget. Now Breen not only had the power but also the financial security to use that power to make The Production Code law in Hollywood.

Joe Breen was soon dictating to the industry’s most powerful producers what they could and could not have in their films. These harried executives let Breen re-write scripts, re-edit films, and even advise actors on their costumes. Breen’s personality, philosophy and imprint found its way into the subtext of every American movie released while his power was at its zenith. A devout Catholic, Breen soon saw himself as a missionary fighting to insure that motion pictures became a means for a nation to learn right from wrong every time someone walked into a movie theatre.

This missionary work had benefits beyond the spiritual. Breen’s $60,000 a year income and perks awarded him a chauffeured limousine, a spacious home for his wife, three sons, three daughters and two servants. He had beach house in Malibu and became part of the Irish Mafia, a Hollywood set that included Pat O’Brian, James Cagney, Spencer Tracy, Irene Dunne and Directors John Ford and Leo McCarey.

Content to hold the reins of power, Breen shunned publicity and let Will Hays and later Hay’s successor Eric Johnston bask in the limelight of press conferences and interviews. Like Irving Thalberg, the head of production at MGM, Breen believed “If you are in a position to give credit to yourself, then you don’t need it.”

*****

For close to 20 years Breen defended his empire with un-paralleled tenacity. As Eric Johnston painfully learned when he tried to replace Breen in 1947, Breen and The Production Code were one and inseparable. Truth was that the Code succeeded because Breen was the only man who knew how to enforce it. After the war when films attempted more realism Breen did bend a bit and allowed serious films more leeway but the Code’s moral imperatives remained unchanged. Only when events beyond Breen’s control chipped away at the code’s defenses did it and Breen began to lose their invincibility.

The division of exhibition from production was a major blow. These divorced theatres were no longer part of MPPA member companies and no longer legally bound to play only Code-certified films. Although there was still a “gentleman’s agreement” between the MPPA and the theatres, by 1950 exhibitors seeing their empty seats growing year by year were prepared to take chances they would never have contemplated during better times.

The Bicycle Thief

The release of The Bicycle Thief was a forecast at what post divestment Hollywood would look like. This acclaimed Italian neo-realist masterpiece directed by Vittoro De Sica not only won an Academy Award for best foreign film but also did big box office at the independent art theatres where it was first shown. The film’s extraordinary success encouraged its distributor to book it into the larger chains and so it was submitted to the PCA. Breen wanted two scenes cut; one taking place in a bordello and the other of a little boy attempting to urinate. The distributor, honoring a promise to De Sica, refused and to Breen’s surprise the film secured bookings with three major chains which hadn’t played a film without a seal film since 1934. What made matters worse, the Legion Of Decency did not support the Code and condemn the film. Breen had made a major miscalculation. He should have factored in more variables before taking a hard line and in not doing so had seriously damaged the Code’s credibility.

A year later the release of another Italian film would also have a profound effect on the future of the Code. A short film by Roberto Rossellini, The Miracle had been judged as sacrilegious by the Catholic Church. After being condemned by the Legion Of Decency and banned by the New York City licensing bureau, it caused a bigger furor than The Bicycle Thief. The case eventually went to the Supreme Court and in a unanimous decision the high court lifted the ban and declared motion pictures a form of free expression protected by the First Amendment. It was a landmark ruling. The days of random and indiscriminate censorship were over.

Breen wasn’t a happy. Without censorship there was no need for self-censorship and, therefore, no need for the Code or Joe Breen.

L-R: Arthur Kim, M. Youngstein, Charlie Chaplin, Robert Benjamin, W. Heinerman

During the fall of 1952 Otto Preminger and F. Hugh Herbert were preparing the film script for The Moon Is Blue. Preminger had already concluded Breen and the Code were paper tigers. The Bicycle Thief was evidence a popular film could be booked into circuit theatres without a Seal and the Supreme Court ruling on The Miracle now made the courts an arena for redress against local censors.

More strategically Preminger had negotiated an agreement with United Artists for the release of Moon. A key provision of that agreement was a clause granting Preminger final cut. Considering Moon‘s potential for controversy it was a risk laden commitment for UA but desperation had made UA a company prepared to take risks.

A year and a half earlier United Artists had almost shut its doors. In a last ditch effort to fend off bankruptcy UA’s owners brought in two entertainment lawyers, Robert Benjamin and Arthur Krim, to salvage the company. Demanding complete independence and 50% of the company the two men had UA stabilized and operating in the black within six months. If UA was ever going to again function as a major film company Krim and Benjamin knew it needed more than just stability; it required revitalization and they had a plan.

Unlike other film companies UA did not have a production facility with huge money gobbling overheads. UA had always functioned simply as a distribution company for producers with completed pictures. Now, while other film companies were struggling to keep those production facilities running in the black, UA had the fiscal freedom to experiment. Instead of “hiring” a film’s creative elements, Krim and Benjamin’s strategy was to enter into partnership with them.

As more and more contract talent was entering the free agent market, film companies were desperately vying for their services. Some companies were even offering profit participation and a degree of creative autonomy. Inevitably the companies were paying the bills and so always had final say and more importantly final cut of every picture they made. Krim and Benjamin realized if they were going to attract top talent they had to raise the ante. Fortunately the two men saw themselves primarily as New York financiers and not Hollywood picture makers. This perspective freed them to rethink the role a film company needed to have in the picture making process. It permitted Krim and Benjamin to offer filmmakers unprecedented creative autonomy.

For the right to distribute their films UA offered producers not only financing but a cut of every dollar earned by the company. In addition, after UA and the producer agreed on story, stars, and production costs, the producer was free to make his movie any way he wanted all the way up to and including final cut.

There was a price for this freedom. Producers, directors and actors had to defer the bulk of their salaries until the film moved into profit. In short, they would take the same risks as UA in hopes of reaping the same financial rewards.

When Krim and Benjamin acquired Moon they achieved an important coup. Preminger was a top director. If their relationship proved creatively and financially beneficial to all parties there was an excellent possibility other top rank independent producers would find UA’s formula equally attractive.

The contract UA offered Preminger was ideal for the director’s purposes. Not only did he have final cut but he would be left alone to make his film anyway he chose. In addition Preminger, Herbert, and even the play’s producers all agreed to defer their salaries and payments. Since the banks demanded a name star before they’d advance a production loan, Preminger agreed to sign one. Like all “above the line” talent the star would work for a deferred salary. These deferments came to just under 500,000 dollars and would enable the production team to keep 75 percent of the film’s profits. If Moon proved a success Preminger and everyone connected with it would earn themselves a fortune.

The budget was set at just under $400,000. This included the cost of a simultaneously filmed German version featuring German actors. This was an insurance measure. The German language market was one of the largest in Europe. In Austria and Germany a picture spoken in German usually out grossed a dubbed or subtitled film by 90%. Thus, if the film proved un-releasable in America there might be a good chance its low production costs could be recouped in Europe with increased German grosses carrying it into profit.

Preminger’s objective at this time was not to make a film unable to earn the Seal, it was to pressure the PCA into bending its rules for Moon. A standard clause still in Preminger’s contract stipulated he must deliver to UA a PCA approved film with either an A or B certificate from the Legion of Decency. The Bicycle Thief and The Miracle had made Breen vulnerable. If a major Hollywood film became a success without the Seal the repercussions for the PCA could be devastating. Therefore, Preminger’s plan was to use the threat of releasing Moon without the seal to bully Breen. He was hoping to push the PCA director into weighing one film against the future of the Code office and force Breen to cave in. But, if this ploy didn’t work, and Breen stood fast, Preminger knew that he would have to make good his threat; he would have to release Moon without the Seal.

Preminger’s first move against the PCA was to go public. In late August 1952, a full four months before he handed the Production Code office Moon‘s completed script, Preminger gave an interview to VARIETY wherein he discussed censorship. Preminger told VARIETY that someday censorship would become as irrelevant in films as it was in theatre. He predicted that the elimination of the Code would not bring on a “spate of ‘dirty’ pictures” but would free American films from a “standardization” created in response to the Code. He went on to tell VARIETY that “pressure groups” did not “picket big box office successes” and “picketing activity” would “not hurt an outstanding picture.” The interview ended with Preminger talking about the real possibility of eliminating censorship.

William Holden and David Niven

During the rest of that fall Preminger and Herbert finished their script and completed casting. Months before Preminger had chosen David Niven for the part of the older roue’, Donald Slater.

In 1952 Niven was in “career difficulty.” For the past four years he had appeared in one box office flop after another and his film career had taken a nose dive. Krim and Benjamin were not pleased with the choice and told Preminger that, not only was Niven “washed up” but his name attached to the picture would hurt the project. Krim even offered to pay the actor off. The director had anticipated their objections and earlier in the year had asked Niven to play Slater during the play’s San Francisco run. He was superb and with that ammunition Preminger persuaded UA to defer to his judgment.

The director was looking for a box office star elsewhere. The previous winter Preminger had played the German camp commandant in STALAG 17. William Holden was the film’s star and the two had gotten to know each other. In 1952 Holden’s career was on the rise. STALAG 17 was still six months away from release but talk was that his performance, after 14 years in the business, would make him a major star.

During Holden’s apprenticeship years he had been shamefully underpaid. In the early days of his film career the young actor was taking home $125 a week while his established co-stars were earning three thousand dollars. By the late 40s he was making more money but nowhere near what he felt would have been fair. When he and his wife, retired actress Brenda Marshall, decided to buy a larger house she was forced to take a part in an Alan Ladd movie so they could manage the down payment.

Now, with Super stardom and big money at hand, the actor felt he had a lot of catching up to do. His recently renegotiated his Paramount contract and was paid $250,000 for just three month’s work a year. The rest of the time he was a free agent. When Preminger approached him to play Donald Gresham, Holden was not only able but anxious to sign the deal. Holden had recently starred in Born Yesterday, another film made from a hit Broadway comedy. A percentage of that blockbuster would have made the actor a mint. This time around things would be different. For a small up front salary and a 20% share of the profits Holden was contracted to work for 11 days of rehearsal and 24 days in front of the camera.

The last major piece of casting was the female lead, Patty O’Neill. The obvious choice would have been as Barbara Bel Geddes. She not only won raves on Broadway but had appeared in a number of films during the late 40s and would be a recognizable name to movie audiences. Instead, Preminger went on instinct and chose Maggie McNamara.

McNamara On Stage In The Moon Is Blue

McNamara had played the lead on the road and in the Chicago company for almost a year before appearing on Broadway as Bel Geddes’ Summer replacement. When Preminger originally cast the inexperienced 21 year old in the play she was lacking in both skill and technique. What she did have, and what she infused Patty with, was a wide eyed innocence that had won over both audience and critics. As the play settled into its long Chicago run her technique improved and the play made her a star.

McNamara On Film in The Moon IS Blue

When McNamara replaced Bel Geddes audiences were able to compare the two performances. Bel Geddes was obviously the superior actress who was able to draw out every nuance and shading in the part. But this command of the part had an odd effect on the character. In Bel Geddes’ hands Patty came off patronizing and seemed almost maternal to the two perspective seducers. McNamara on the other hand was more childlike and vulnerable. What appeared in Bel Geddes to be patronizing appeared in McNamara as an innocent’s attempt at sophistication. There was more tension on the stage and the play came off sexier. If Preminger could draw this quality out of McNamara on the screen he knew he’d have himself a hit.

In December 1952, when Preminger and Herbert submitted their script to the Breen office, everything was moving along smoothly. All of the production’s elements had come together and the film had a January start date.

Preminger and Herbert’s script was an almost word for word translation of the play. A few characters had been added. A few transitions written but the script contained all the play’s sharp and for the screen, frank and explicit dialogue. Preminger had been in Hollywood long enough to know what Breen’s reaction would be.

*****

In November 1951 a persistent lung ailment sent Breen under the knife. He lost part of a lung and although he recuperated quickly he was forced to acknowledge that years of overwork had caught up to him. Breen listened to his doctors, lightened up his work load and left the day-to-day operation of the Code office to his assistant Geoffrey Shurlock. Breen was now there to advise, set overall policy and wage the important battles.

Shurlock was more liberal than Breen and, although only a few years separated them, was more in touch with the times. He knew, more than Breen did, that the Code needed to be updated if it was ever going to survive. Nonetheless, as a subordinate of Breen’s Shurlock did not allow his personal feelings to reflect on his decisions as a Code functionary. Breen set the tone and Shurlock followed. Personally Shurlock liked The Moon Is Blue. He had seen the play and it wouldn’t have been a problem for him to give the film The Seal.

But Joe Breen was a different matter. What bothered Breen was not just the play’s language, with its references to virgins and seduction, what he found objectionable was the entire tone and premise of the play. Moon presented a moral landscape completely opposed to the intent and philosophy of the Production Code. Its characters were preoccupied from beginning to end with what the Code termed a “low form of sex relationship” and presented these relationships as an acceptable mode of behavior.

The presentation of “low sex” was not in itself unusual. Five years earlier David Selznick’s mammoth production Duel In The Sun was populated with characters primarily motivated by sexual impulse. But this “low sex” was in the context of a heavy, brooding western melodrama in which the leading characters’ frenzied carnal desires brought them, in the film’s climactic shoot-out, to their destruction. Indulgence in this “low sex” was punished and, according to the rules of the Code, a moral lessen had been taught.

Moon was a different matter. It was a comedy and the Code clearly specified the topic of seduction was not to be made light of or the object of ridicule. Yet ridicule was a key element in the success of Herbert’s play. It poked fun at each character and their position on the moral spectrum. It was precisely Herbert’s intention to make them and their attitudes appear foolish so that the play’s lack of a “moral point of view” forced audiences to discover their own. It is this kind of sophisticated writing that makes for good theatre. The Production Code could not permit something as open ended as Moon. It required every film to contain a moral point of view prescribed by The Code. This is what had bristled filmmakers from the moment the Code was imposed on them. It didn’t allow filmmakers to explore the human condition in all its shadings. Every film had to fit into a narrow pattern on a Breen prescribed and approved moral landscape. Rights were rewarded. Wrongs were punished. The family was sacred. On and on it went, as it forced films into the role of a Sunday school teacher.

It was impossible for Breen to approve the script to Moon. He saw this film as a direct and premeditated attack on the Code. It struck at the very heart of the Code’s philosophy and opposed everything Breen had been fighting to create for almost twenty years. So, he returned the script to Preminger with a letter outlining his objections and waited for Preminger’s reply.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jnmk0LQpt7E

What more can ANYONE say, Joe – you are a master at this kind of writing. All I ever heard about this from Mom was just about the ‘Hays office’ cutting out parts of films. Nothing I remember at all. zzzzzzzzzzzzzzz