JOHN BARRYMORE AND ALL MY CHILDREN

JOHN BARRYMORE AND ALL MY CHILDREN

Early on it was suggested—for the blog at least— that I post sections from The Purple Diaries which had been deleted during the editing process. Presumably this would add up to a sort of “deleted scenes” kind of thing you see on DVDs and Blu-rays for fillm directors but this time it would be for a writer–me. Unfortunately, most of the cuts made during editing were small; a line here, a redundancy there with a certain degree of rewriting. But, there was one extended section cut that, I believe, can stand by itself.

It dealt with John Barrymore during 1939 and1940 performing on stage one last time in a travesty of a play called All My Children. I had cut these passages with great reluctance. And here it becomes interesting. As an editor, I knew my editor would want it out and I knew this because as an editor myself—if this book had been given to me to revise—it would probably have been the first thing that I would take out. Not only was it tangential but completely unnecessary to a compelling and focused telling of the Mary Astor story. But the writer—and not the editor— in me was reluctant to give it up. To put it bluntly, I had fallen in love with the passage.

It had been written in a moment when the muse was with me full throttle and the words literally few out of as if I was inspired. In it, I said everything that I wanted to say, exactly the way I wanted it said and it expressed my point of view completely to my satisfaction. Truth be said, everyone who knew John Barrymore loved the man. He never took himself seriously, didn’t suffer fools gladly and was both brilliant and captivating all at the same time even when he was being a downright scoundrel . For Mary Astor, who had been seduced by the man at age 17 and despite the fact that he had dropped her for another woman, Barrymore would remain the great love of Astor’s life. I felt what I had written captured the essence of the man.

But out it went and of the here it is.

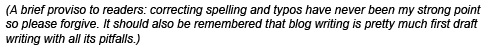

BARRYMORE TRYING TO LEARN HIS LINES

By 1939, deep in in debt and desperate for money, John Barrymore—against everyone’s advice—returned to the stage after a 15 year absence in a play titled My Dear Children which a potential producer called, “One of the worst scripts he ever read.” Barrymore’s assement was a bit kinder. “It’s no Desire Under The Elms.” Nevertheless, with a $4,500 weekly paycheck if the play proved a success, Barrymore was in no position to refuse. By this time his wife Elaine Barry, at Barrymore’s request—recent divorce suit having been dropped—was back with the actor playing a part in the play.

BARRYMORE WITH ELAINE BARRY

The tryout for My Dear Children’s took place in March 1939 in Princeton New Jersey. Forgetting his lines, Barrymore landed up adlibbing through most of the performance and these adlibs were so hilarious that they literally brought the house down. What the audience was seeing was John Barrymore at his absolute funniest and this adlibbing would continue throughout the rest of the run—especially when the actor was imbibed which was most of the time. Many were later incorporated into the published version of the play.

Barrymore lampooned the play, his part and most of all himself and in the process delighted audiences. Albert Einstein happened to be at the Princeton performance and laughed and applauded like everyone else. Nevertheless, many friends, actors and even admirers who had known Barrymore at the height of his powers–considered the greatest actor alive–found the play and what Barrymore was doing in it a travesty and more importantly a public debasement of a great actor’s talent. There was only one problem with this assessment. John Barrymore was no longer the man or the actor he had once been. Years of drinking and hedonism had taken their toll: prematurely aged, suffering from congested heart disease he now had a memory so impaired that he simply couldn’t remember lines. Contrary to what so many believed, John Barrymore wasn’t making a fool of himself but, in an act of immense personal courage, was “giving them all he had” to give. At this point in his life all John Barrymore had to give was John Barrymore, foibles and all. In the process he single handedly transformed this shoddy little play into a theatrical event in a feat that was nothing less than heroic.

About this performance biographer John Kobler would write, “Only a comedian of John’s extraordinary technical equipment could have roused an audience to shrieks of laughter with such waggery by an accompanying grimace or gesture. Together with clowning, mugging, grunts, snorts, rumbles, yawns, bleats, leers, smirks, ogles, roars, squirts, eye rolling, eyebrow-twitching, strutting, mincing, pouncing, staggering, hip-skipping and jumps, profanity, obscenity and general horseplay, Barrymore would turn a vapid farce into a freakish smash hit unique in theatre annals.” As a result My Dear Children played to packed audiences on the road for the next 8 months and ran for 33 weeks in Chicago alone.

By April 1939 Mr. and Mrs. Barrymore weren’t speaking again and by May Mrs. Barrymore was out of the show, again filing for a divorce. If that wasn’t enough, during the run, in addition to his heart problems, the actor endured a variety of physical ailments including “blood clots, hand tremors, bone inflammation, piles and dropsy” and even suffered a coronary but he was on that stage every night.

BARRYMORE WITH BARRY

It took months, but the play allowed Barrymore to pay off his debts and on January 20th, 1940 My Dear Children finally opened in New York. Due to its reputation, “the advance sale was one of the biggest in Broadway History.” On opening night the moment that Barrymore walked on stage the entire audience stood and applauded for a full five minutes and did the same at the end of the show. They certainly weren’t applauding this travesty of a play but, instead, for the stupendous work Barrymore had done on the Broadway stage years earlier and what he and that work had meant to them and the theater.

The New York reviews were of course eviscerating, all accept The New York Times’ notice. Brooks Atkinson wrote that, although Barrymore “is a ravished figure now, but the fact remains that he can still act like a man whom the gods have generously endowed and like a man who knows the art and business of stage expression.”

Three nights later Barrymore collapsed from sheer physical exhaustion but by weeks’ end was back on stage. The play ran four months on Broadway to packed houses. It could have run longer but Barrymore had received a film offer and the money was simply too good to refuse—$200,000 for a single movie.

After reconciling for the umpteenth time with Elaine Barrie the two finally divorced on November 27, 1940, almost 5 years after Miss Barrie had forced her way into Barrymore’s life. In a strange twist of fate, during the court proceeding, Barrymore was represented by none other than Roland Rich Woolley the very same attorney who had represented Mary Astor during her custody battle.

Barrymore would make four more inconsequential films before his death two years later in 1942 at age 60.

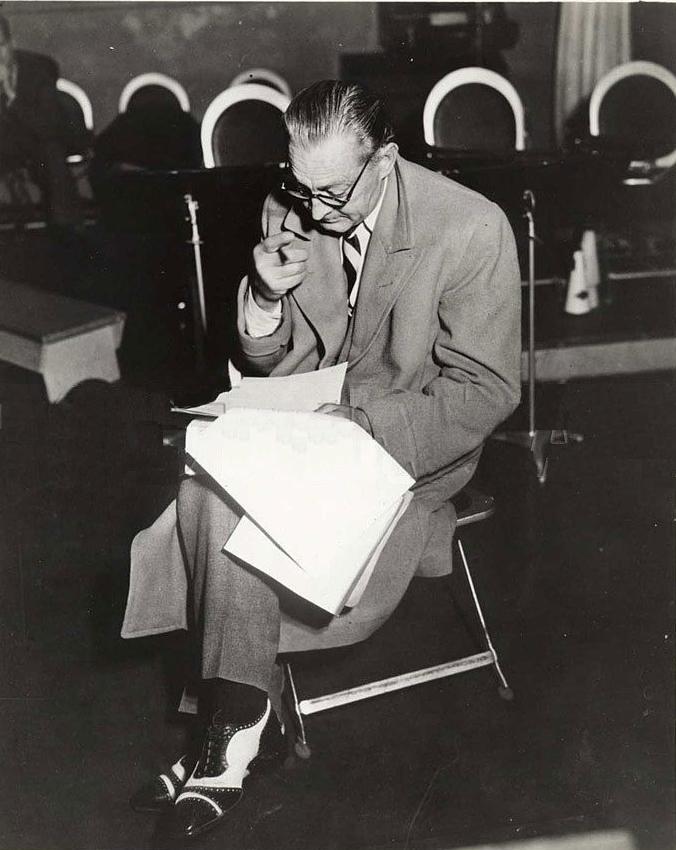

1922 DRAWING BY JOHN SINGER SARGENT OF BARRYMORE AS HAMLET

Years before his death, Barrymore had watched John Gielgud’s interpretation of Hamlet, a role Barrymore had performed in the 1920s and for which he had been celebrated as the greatest actor alive. Following Gielgud’s performance Barrymore confided to the actor that he, Barrymore, had been a transitional actor. He had brought psychology to the stage and replaced stage pontification with living breathing characters. Others, like Gielgud, had taken up the mental and would extend what he had done and in doing so transform acting into something that the stage had never seen before. In short, what Barrymore had begun is what, today, we call modern acting and with his passing that link between past and present passed with him. To quote Shakespeare, “never would there be his like again.”

Below is an interview given by Barrymore during the run of All My Children

(A brief proviso to readers: correcting spelling and typos have never been my strong point so please forgive. It should also be remembered that blog writing is pretty much first draft writing with all its pitfalls.)

Good stuff, Joe – and to think this ol’ Boy might have been my father – but thank heavens, he was not. With all his acclaim, he seemed like the loneliest man on the Planet. And so unhealthy! More to be pitied than censured, that’s for sure.